30 min to read

Introduction to System.Threading.Channels

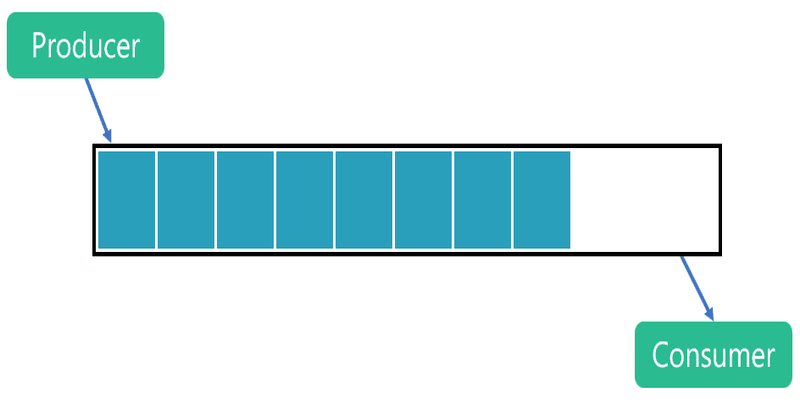

A synchronisation concept which supports passing data between producers and consumers.

“Producer/consumer” problems are everywhere, in all facets of our lives. A line cook at a fast food restaurant, slicing tomatoes that are handed off to another cook to assemble a burger, which is handed off to a register worker to fulfill your order, which you happily gobble down. Postal drivers delivering mail all along their routes, and you either seeing a truck arrive and going out to the mailbox to retrieve your deliveries or just checking later in the day when you get home from work. An airline employee offloading suitcases from a cargo hold of a jetliner, placing them onto a conveyer belt, where they’re shuttled down to another employee who transfers bags to a van and drives them to yet another conveyer that will take them to you. And a happy engaged couple preparing to send out invites to their wedding, with one partner addressing an envelope and handing it off to the other who stuffs and licks it.

As software developers, we routinely see happenings from our everyday lives make their way into our software, and “producer/consumer” problems are no exception. Anyone who’s piped together commands at a command-line has utilized producer/consumer, with the stdout from one program being fed as the stdin to another. Anyone who’s launched multiple workers to compute discrete values or to download data from multiple sites has utilized producer/consumer, with a consumer aggregating results for display or further processing. Anyone who’s tried to parallelize a pipeline has very explicitly employed producer/consumer. And so on.

All of these scenarios, whether in our real-world or software lives, have something in common: there is some vehicle for handing off the results from the producer to the consumer. The fast food employee places the completed burgers in a stand that the register worker pulls from to fill the customer’s bag. The postal worker places mail into a mailbox. The engaged couple’s hands meet to transfer the materials from one to the other. In software, such a hand-off requires a data structure of some kind to facilitate the transaction, storage that can used by the producer to transfer a result and potentially buffer more, while also enabling the consumer to be notified that one or more results are available. Enter System.Threading.Channels.

What is a Channel?

I often find it easiest to understand some technology by implementing a simple version myself. In doing so, I learn about various problems implementers of that technology may have had to overcome, trade-offs they may have had to make, and the best way to utilize the functionality. To that end, let’s start learning about System.Threading.Channels by implementing a “channel” from scratch.

A channel is simply a data structure that’s used to store produced data for a consumer to retrieve, and an appropriate synchronization to enable that to happen safely, while also enabling appropriate notifications in both directions. There is a multitude of possible design decisions involved. Should a channel be able to hold an unbounded number of items? If not, what should happen when it fills up? How critical is performance? Do we need to try to minimize synchronization? Can we make any assumptions about how many producers and consumers are allowed concurrently? For the purposes of quickly writing a simple channel, let’s make simplifying assumptions that we don’t need to enforce any particular bound and that we don’t need to be overly concerned about overheads. We’ll also make up a simple API.

To start, we need our type, to which we’ll add a few simple methods:

public sealed class Channel<T>

{

public void Write(T value);

public ValueTask<T> ReadAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

}

Our Write method gives us a method we can use to produce data into the channel, and our ReadAsync method gives us a method to consume from it. Since we decided our channel is unbounded, producing data into it will always complete successfully and synchronously, just as does calling Add on a List

Now we just need to implement these two methods. To start, we’ll add two fields to our type: one to serve as the storage mechanism, and one to coordinate between the producers and consumers:

private readonly ConcurrentQueue<T> _queue = new ConcurrentQueue<T>();

private readonly SemaphoreSlim _semaphore = new SemaphoreSlim(0);

We use a ConcurrentQueue

Our Write method is simple. It just needs to store the data into the queue and increment the SemaphoreSlim‘s count by “release”ing it:

public void Write(T value)

{

_queue.Enqueue(value); // store the data

_semaphore.Release(); // notify any consumers that more data is available

}

And our ReadAsync method is almost just as simple. It needs to wait for data to be available and then take it out.

public async ValueTask<T> ReadAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

await _semaphore.WaitAsync(cancellationToken).ConfigureAwait(false); // wait

bool gotOne = _queue.TryDequeue(out T item); // retrieve the data

Debug.Assert(gotOne);

return item;

}

Note that because no other code could be manipulating the semaphore or the queue, we know that once we’ve successfully waited on the semaphore, the queue will have data to give us, which is why we can just assert that the TryDequeue method successfully returned one. If those assumptions ever changed, this implementation would need to become more complicated.

And that’s it: we have our basic channel. If all you need are the basic features assumed here, such an implementation is perfectly reasonable. Of course, the requirements are often more significant, both on performance and on APIs necessary to enable more scenarios.

Now that we understand the basics of what a channel provides, we can switch to looking at the actual System.Threading.Channel APIs.

Introducing System.Threading.Channels

The core abstractions exposed from the System.Threading.Channels library are a writer:

public abstract class ChannelWriter<T>

{

public abstract bool TryWrite(T item);

public virtual ValueTask WriteAsync(T item, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

public abstract ValueTask<bool> WaitToWriteAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

public void Complete(Exception error);

public virtual bool TryComplete(Exception error);

}

and a reader:

public abstract class ChannelReader<T>

{

public abstract bool TryRead(out T item);

public virtual ValueTask<T> ReadAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

public abstract ValueTask<bool> WaitToReadAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

public virtual IAsyncEnumerable<T> ReadAllAsync([EnumeratorCancellation] CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

public virtual Task Completion { get; }

}

Having just completed our own simple channel design and implementation, most of this API surface area should feel familiar. ChannelWriter

Of course, there are situations where code may not want to produce a value immediately; if producing a value is expensive or if a value represents an expensive resource (maybe it’s a big object that would take up a lot of memory, or maybe it stores a bunch of open files) and if there’s a reasonable chance the producer is running faster than the consumer, the producer may want to delay producing a value until it knows a write will be immediately successful. For that, and related scenarios, there’s WaitToWriteAsync. A producer can await for WaitToWriteAsync to return true, and only then choose to produce a value that it then TryWrites or WriteAsyncs to the channel.

Note that WriteAsync is virtual. Some implementations may choose to provide a more optimized implementation, but with abstract TryWrite and WaitToWriteAsync, the base type can provide a reasonable implementation, which is only slightly more sophisticated than this:

public async ValueTask WriteAsync(T item, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

while (await WaitToWriteAsync(cancellationToken).ConfigureAwait(false))

if (TryWrite(item))

return;

throw new ChannelCompletedException();

}

In addition to showing how WaitToWriteAsync and TryWrite can be used, this highlights a few additional interesting things. First, the while loop is present here because channels by default can be used by any number of producers and any number of consumers concurrently. If a channel had an upper bound on how many items it could store, and if multiple threads are racing to write to the buffer, it’s possible for two threads to be told “yes, there’s space” via WaitToWriteAsync, but then for one of them to lose the race condition and have TryWrite return false, hence the need to loop around and try again. This example also highlights why WaitToWriteAsync returns a ValueTask

Most of the members on ChannelReader

public async ValueTask<T> ReadAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

while (true)

{

if (!await WaitToReadAsync(cancellationToken).ConfigureAwait(false))

throw new ChannelClosedException();

if (TryRead(out T item))

return item;

}

}

There are a variety of typical patterns for how one consumes from a ChannelReader

while (true)

{

T item = await channelReader.ReadAsync();

Use(item);

}

Of course, if the stream of values isn’t infinite and the channel will be marked completed at some point, once consumers have emptied the channel of all its data subsequent attempts to ReadAsync from it will throw. In contrast TryRead will return false, as will WaitToReadAsync. So, a more common consumption pattern is via a nested loop:

while (await channelReader.WaitToReadAsync())

while (channelReader.TryRead(out T item))

Use(item);

The inner “while” could have instead been a simple “if”, but having the tight inner loop enables a cost-conscious developer to avoid the small additional overheads of WaitToReadAsync when an item is already available such that TryRead will successfully consume an item. In fact, this is the exact pattern employed by the ReadAllAsync method. ReadAllAsync was introduced in .NET Core 3.0, and returns an IAsyncEnumerable

await foreach (T item in channelReader.ReadAllAsync())

Use(item);

And the base implementation of the virtual method employs the exact pattern nested-loop pattern shown previously with WaitToReadAsync and TryRead:

public virtual async IAsyncEnumerable<T> ReadAllAsync(

[EnumeratorCancellation] CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

while (await WaitToReadAsync(cancellationToken).ConfigureAwait(false))

while (TryRead(out T item))

yield return item;

}

The final member of ChannelReader

Built-In Channel Implementations

Ok, so we know how to write to writers and read from readers… but from where do we get those writers and readers?

The Channel<TWrite, TRead> type exposes a Writer property and a Reader property that returns a ChannelWriter

public abstract class Channel<TWrite, TRead>

{

public ChannelReader<TRead> Reader { get; }

public ChannelWriter<TWrite> Writer { get; }

}

This base abstract class is available for the niche uses cases where a channel may itself transform written data into a different type for consumption, but the vast majority use case has TWrite and TRead being the same, which is why the majority use happens via the derived Channel type, which is nothing more than:

public abstract class Channel<T> : Channel<T, T> { }

The non-generic Channel type then provides factories for several implementations of Channel

public static class Channel

{

public static Channel<T> CreateUnbounded<T>();

public static Channel<T> CreateUnbounded<T>(UnboundedChannelOptions options);

public static Channel<T> CreateBounded<T>(int capacity);

public static Channel<T> CreateBounded<T>(BoundedChannelOptions options);

}

The CreateUnbounded method creates a channel with no imposed limit on the number of items that can be stored (of course at some point it might hit the limits of the memory, just as with List

In contrast, the CreateBounded method creates a channel with an explicit limit maintained by the implementation. Prior to reaching this capacity, just as with CreateUnbounded, TryWrite will return true and both WriteAsync and WaitToWriteAsync will complete synchronously. But once the channel fills up, TryWrite will return false, and both WriteAsync and WaitToWriteAsync will complete asynchronously, only completing their returned tasks when space is available, or another producer signals the channel’s completion. (It should go without saying that all of these APIs that accept a CancellationToken can also be interrupted by cancellation being requested).

Both CreateUnbounded and CreateBounded have overloads that accept a ChannelOptions-derived type. This base ChannelOptions provides options that can control any channel’s behavior. For example, it exposes SingleWriter and SingleReader properties, which allow the creator to indicate constraints they’re willing to accept; a creator sets SingleWriter to true to indicate that at most one producer will be accessing the writer at a time, and similarly sets SingleReader to true to indicate that at most one consumer will be accessing the reader at a time. This allows for the factory methods to specialize the implementation that’s created, optimizing it based on the supplied options; for example, if the options passed to CreateUnbounded specifies SingleReader as true, it returns an implementation that not only avoids locks when reading, it also avoids interlocked operations when reading, significantly reducing the overheads involved in consuming from the channel. The base ChannelOptions also exposes an AllowSynchronousContinuations property. As with SingleReader and SingleWriter, this defaults to false, and a creator setting it to true means signing up for some optimizations that also have strong implications for how producing and consuming code is written. Specifically, AllowSynchronousContinuations in a sense allows a producer to temporarily become a consumer. Let’s say there’s no data in a channel and a consumer comes along and calls ReadAsync. By awaiting the task returned from ReadAsync, that consumer is effectively hooking up a callback to be invoked when data is written to the channel. By default, that callback will be invoked asynchronously, with the producer writing the data to the channel and then queueing the invocation of that callback, which allows the producer to concurrently go on its merry way while the consumer is processed by some other thread. However, in some situations it may be advantageous for performance to allow that producer writing the data to also itself process the callback, e.g. rather than TryWrite queueing the invocation of the callback, it simply invokes the callback itself. This can significantly cut down on overheads, but also requires great understanding of the environment, as, for example, if you were holdling a lock while calling TryWrite, with AllowSynchronousContinuations set to true, you might end up invoking the callback while holding your lock, which (depending on what the callback tried to do) could end up observing some broken invariants your lock was trying to maintain.

The BoundedChannelOptions passed to CreateBounded layers on additional options specific to bounding. In addition to the maximum capacity supported by the channel, it also exposes a BoundedChannelFullMode enum that indicates the behavior writes should experience when the channel is full:

public enum BoundedChannelFullMode

{

Wait,

DropNewest,

DropOldest,

DropWrite

}

The default is Wait, which has the semantics already discussed: TryWrite on a full channel returns false, WriteAsync will return a task that will only complete when space became available and the write could complete successfully, and similarly WaitToWriteAsync will only complete when space becomes available. The other three modes instead enable writes to always complete synchronously, dropping an element if the channel is full rather than introducing back pressure. DropOldest will remove the “oldest” item (wall-clock time) from the queue, meaning whichever element would next be dequeued by a consumer. Conversely, DropNewest will remove the newest item, whichever element was most recently written to the channel. And DropWrite drops the item currently being written, meaning for example TryWrite will return true but the item it added will immediately be removed.

Performance

From an API perspective, that’s pretty much it. The abstractions exposed are relatively simple, which is a large part of where the power of the library comes from. Simple abstractions and a few concrete implementations that should meet the 99.9% use cases of developers’ needs. Of course, the surface area of the library might suggest that the implementation is also simple. In truth, there’s a decent amount of complexity in the implementation, mostly focused on enabling great throughput while enabling simple consumption patterns easily used in consuming code. The implementation, for example, goes to great pains to minimize allocations. You may have noticed that many of the methods in the surface area return ValueTask and ValueTask

Consider this benchmark:

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Running;

using System.Threading.Channels;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

[MemoryDiagnoser]

public class Program

{

static void Main() => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Program>();

private readonly Channel<int> s_channel = Channel.CreateUnbounded<int>();

[Benchmark]

public async Task WriteThenRead()

{

ChannelWriter<int> writer = s_channel.Writer;

ChannelReader<int> reader = s_channel.Reader;

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000_000; i++)

{

writer.TryWrite(i);

await reader.ReadAsync();

}

}

}

Here we’re just testing the throughput and memory allocation on an unbounded channel when writing an element and then reading out that element 10 million times, which means an element will always be available for the read to consume and thus the read will always complete synchronously, yielding the following results on my machine (the 72 bytes shown in the Allocated column is for the single Task returned from WriteThenRead):

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WriteThenRead | 527.8 ms | 2.03 ms | 1.90 ms | – | – | – | 72 B |

But now let’s change it slightly, first issuing the read and only then writing the element that will satisfy it. In this case, reads will always complete asynchronously because the data to complete them will never be available:

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Running;

using System.Threading.Channels;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

[MemoryDiagnoser]

public class Program

{

static void Main() => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Program>();

private readonly Channel<int> s_channel = Channel.CreateUnbounded<int>();

[Benchmark]

public async Task ReadThenWrite()

{

ChannelWriter<int> writer = s_channel.Writer;

ChannelReader<int> reader = s_channel.Reader;

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000_000; i++)

{

ValueTask<int> vt = reader.ReadAsync();

writer.TryWrite(i);

await vt;

}

}

}

which on my machine for 10 million writes and reads yields results like this:

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ReadThenWrite | 881.2 ms | 4.60 ms | 4.30 ms | – | – | – | 72 B |

So, there’s some more overhead when every read completes asynchronously, but even here we see zero allocations for the 10 million asynchronously-completing reads (again, the 72 bytes shown in the Allocated column is for the Task returned from ReadThenWrite)!

Combinators

Generally consumption of channels is simple, using one of the approaches shown earlier. But as with IEnumerables, it’s also possible to implement various kinds of operations over channels to accomplish a specific purpose. For example, let’s say I want to wait for the first element to arrive from either of two supplied readers; I could write something like this:

public static async ValueTask<ChannelReader<T>> WhenAny<T>(

ChannelReader<T> reader1, ChannelReader<T> reader2)

{

var cts = new CancellationTokenSource();

Task<bool> t1 = reader1.WaitToReadAsync(cts.Token).AsTask();

Task<bool> t2 = reader2.WaitToReadAsync(cts.Token).AsTask();

Task<bool> completed = await Task.WhenAny(t1, t2);

cts.Cancel();

return completed == t1 ? reader1 : reader2;

}

Here we’re just calling WaitToReadAsync on both channels, and returning the reader for whichever one completes first. One of the interesting things to note about this example is that, while ChannelReader

Relationship to the rest of .NET Core

System.Threading.Channels is part of the .NET Core shared framework, meaning a .NET Core app can start using it without installing anything additional. It’s also available as a separate NuGet package, though the separate implementation doesn’t have all of the optimizations that built-in implementation has, in large part because the built-in implementation is able to take advantage of additional runtime and library support in .NET Core.

It’s also used by a variety of other systems in .NET. For example, ASP.NET uses channels as part of SignalR as well as in its Libuv-based Kestrel transport. Channels are also used by the upcoming QUIC implementation currently being developed for .NET 5.

If you squint, the System.Threading.Channels library also looks a bit similar to the System.Threading.Tasks.Dataflow library that’s been available with .NET for years. In some ways, the dataflow library is a superset of the channels library; in particular, the BufferBlock

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes;

using BenchmarkDotNet.Running;

using System.Threading.Channels;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using System.Threading.Tasks.Dataflow;

[MemoryDiagnoser]

public class Program

{

static void Main() => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Program>();

private readonly Channel<int> _channel = Channel.CreateUnbounded<int>();

private readonly BufferBlock<int> _bufferBlock = new BufferBlock<int>();

[Benchmark]

public async Task Channel_ReadThenWrite()

{

ChannelWriter<int> writer = _channel.Writer;

ChannelReader<int> reader = _channel.Reader;

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000_000; i++)

{

ValueTask<int> vt = reader.ReadAsync();

writer.TryWrite(i);

await vt;

}

}

[Benchmark]

public async Task BufferBlock_ReadThenWrite()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000_000; i++)

{

Task<int> t = _bufferBlock.ReceiveAsync();

_bufferBlock.Post(i);

await t;

}

}

}

| Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel_ReadThenWrite | 878.9 ms | 0.68 ms | 0.60 ms | 72 B | – | – | 72 B |

| BufferBlock_ReadThenWrite | 20,116.4 ms | 192.82 ms | 180.37 ms | 1184000.0000 | 2000.0000 | – | 7360000232 B |

This is in no way meant to suggest that the System.Threading.Tasks.Dataflow library shouldn’t be used. It enables developers to express succinctly a large number of concepts, and it can exhibit very good performance when applied to the problems it suits best. However, when all one needs is a hand-off data structure between one or more producers and one or more consumers you’ve manually implemented, System.Threading.Channels is a much simpler, leaner bet.